Wall Street Journal Raves About Hillrock Estate

Bourbon, Made in N.Y.

Ralph Gardner Jr. Gets Into the Spirit With Jeffrey Baker, Owner of the Hudson Valley Distillery Hillrock

By Ralph Gardner Jr.

Nov. 11, 2013 9:42 p.m. ET

Wall Street Journal

I was under the impression there was a reason bourbon is made in Kentucky: that there was something fun-loving about the climate or the soil that found its way into the alcohol. But Jeffrey Baker, the owner of Hillrock, a Hudson Valley distillery situated about two hours north of the city, told me that isn't necessarily so.

"In the 1820s, there were probably 2,000 farm distilleries in New York," he explained. "That was the case around the country. In 1800, George Washington had the largest distillery in the U.S. It was pretty much his most profitable farming venture."

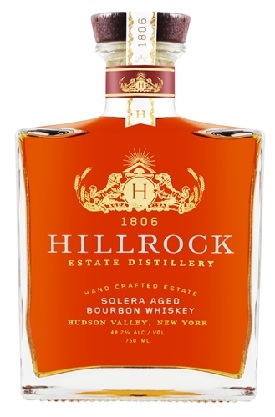

Mr. Baker, a 53-year-old investment banker, makes delightful Solera bourbon. Launched in 2012, it's finished in Oloroso Sherry casts, a Spanish technique that give it depth and a sweet, slightly spicy flavor. He also makes a single malt whiskey, rye and a historically accurate, unaged George Washington rye whiskey created in partnership with Mt. Vernon. All told, the distillery produces about 5,000 cases annually.

"Our operation is very similar to what George Washington was doing at the time," Mr. Baker said. "The scale and the field-to-glass."

The distiller's hilltop 1806 home, with lovely views of both the Berkshires and his malt house, are surrounded by the fields that provide some of the grains that go into his liquor (hence the description "field-to-glass"). The corn used to make the bourbon comes from local farms.

For the sake of full disclosure, I should state that I'm not a bourbon connoisseur. It's a little too sweet to be a staple of my drinking diet. Instead, I'll have a single malt (or two) and, just before dinner, top it off with a shot of bourbon. I'm not picky. Jim Beam will do. It adds a festive note and serves as a punctuation mark, informing my brain and taste buds that it's time to head into the next phase of the evening.

But during a subsequent tasting of all Hillrock's beverages, I realized the bourbon was special. (Not that the single malt or rye was anything to sniff at, except to absorb the flavor notes.) It was smooth and delicate. In other words, at $80 a bottle, it would be a sin to waste it on me.

Mr. Baker said he worked on farms while growing up. "When I moved to New York, I was sort of missing something," he explained. "Pretty quickly I decided to do some farming. I set up one of the earliest rotational grazing herds."

This was in Washington County, an additional hour or two north of the city. It was also the '80s, before anyone had heard of locavores. "People weren't ready yet," Mr. Baker said. "They wouldn't pay a premium."

His distilling venture started after he bought a Georgian home in the Lake George area. Rather than live there, he disassembled it, moved it about a hundred miles south to Ancram in Columbia County, reassembled it and meticulously restored it.

Before I proceed, several thoughts, or at least one, about people like Jeff Baker—he has an MBA from Wharton and also master's degrees in both architecture and city planning—who I run into occasionally in this line of work: Where do they find the time, energy and ambition? Are they as impressive as they seem, or are they simply expressing some deep-seated insecurity through their accomplishments?

I wouldn't purchase a house only to take it apart. Couldn't he find acceptable shelter atop a hill without inviting all the additional headaches? I'm still recuperating and basking in the heightened self-esteem from a trail I blazed through the woods. And that was a decade ago.

"I guess I don't like golf," Mr. Baker explained as we sat by his fireplace.

The idea of becoming a distiller started to crystallize as he researched his new home and discovered that Israel Harris, the fellow who built the house, had been a Revolutionary War captain who fought with the Green Mountain Boys. "He ended up being a successful grain merchant," Mr. Baker said. "In the 1820s, New York was producing two-thirds of the barley for the whole country and a significant portion of the rye. It was clear you could grow grass in the area. It started me thinking what we could do with grain."

"I have always been a big wine and spirits person," he added, his MBA whispering that the highest mark up came from turning grain into alcohol. Also, that people might be willing to pay a premium for locally grown spirits in the same way they're now mad for fruit, vegetables and grass-fed beef.

The only caveat: "I wanted it to be world class," Mr. Baker said.

So he tracked down Dave Pickerell, a master distiller who had worked at Maker's Mark for 14 years. "I called him up and said, 'Is it true nobody has done a field-to-glass whiskey operation in the States?' He thought it was a great idea."

The day-to-day operation is run by Tim Welly, who previously worked as the cellar master at Millbrook Winery. "Wine makers tend to be more careful whiskey makers," Mr. Baker argued.

I'll resist the temptation to get into the weeds, or rather the six-acre rye field that stands between Mr. Baker's home and his new malt house, for fear of describing the details of the operation inaccurately. Suffice it to say that if I thought his home was impressive, you should see the distillery and malt house. It's more than ready for its Architectural Digest close-up. "It's the first purpose-built malt house in the U.S. since before Prohibition," Mr. Baker boasted.

The handsome tool that Mr. Welly was using to rake the malt was made by a sculptor. "It's not like you can go to a hardware store to get malting equipment anymore," Mr. Baker explained.

I am too discreet to ask what the distillery had cost so far—but did so anyway. "A number of million dollars," Mr. Baker said. But he noted that a ton of malt creates $60,000 worth of whiskey. "In terms of economics it's probably the highest-value farming around other than marijuana."

He added: "At this scale, you can be pretty profitable. Everything we made has been sold out pretty quickly."

He wasn't exaggerating. After our tasting, I discovered, much to my disappointment, that there wasn't any bourbon available to purchase. Fortunately, a new batch should be ready before Thanksgiving.

—ralph.gardner@wsj.com

Read more at:

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304644104579192091921065358

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

Subscribe to Post Comments [Atom]

<< Home